Ode to a Victorian Gardener and Poetess: Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

“If we love flowers are we not born again every Day", Emily Dickinson to Mrs. George S. Dickerman, 1886

One of the earliest gifts my mother gave me was a book of poems by Emily Dickinson. It was a hardcover gold leafed paged coral and pine green designed book entitled, 'Collected Poems Of Emily Dickinson'. I was ten years old and the first poem to stand out in my memory was:

I'm nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there's a pair of us -- don't tell;

They'd banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

As you can tell, I was born a pessimist with optimistic yearnings! I leafed through my treasured, well-worn hardcover today and page numbers with favorite poems were circled and my ten year old self made notes in the margins. My mom would be proud, indeed!

So it is with great love and a deep abiding admiration for one of America's best Poets of the Victorian era, I give you Emily Dickinson: Gardener and Poetess...

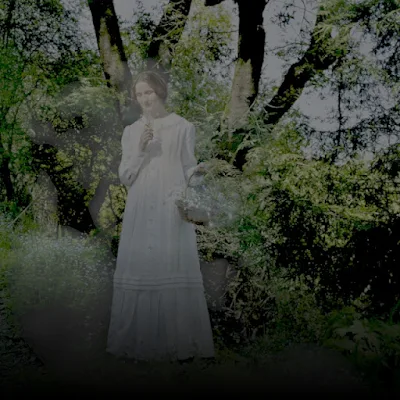

Emily Dickinson's 19th century New England garden

During her lifetime, Emily Dickinson was more widely known as a gardener, than as a poet. Her poetry for the most part was privately published and often enclosed in letters pinned together by flowers or in bouquets that made the poem concealed at the flowers’ center and the flowers themselves one message. John Ruskin’s ‘Modern Painters’ deeply influenced Emily Dickinson because she said he was a geologist first and an artist later. So before she wrote poems, she gathered, tended, categorized and pressed flowers. After poetry writing became her main job, cultivating bulbs, plants, and flowers within a portion of her father’s land as in the glass enclosure of a conservatory, built just for her, remained a favorite occupation.

Emily Dickinson's Herbarium, digital facsimile. By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University

Dickinson would explore nearby woodlands and meadows for new flowers to collect. Ultimately, she pressed over 400 specimens into a leather-bound album, arranging her specimens artistically, labeling sixty-five of the four hundred with the genus and species according to the Linnaean system of classification. Though only a few of Dickinson's poems were printed during her lifetime, many people remembered receiving one of them, often tucked into an exquisite bouquet that she had grown and arranged herself. These interests can be traced in her literary work as well. Indeed, more than two-thirds of Dickinson's lyrical letters to family and chosen friends and one-third of her brilliantly idiosyncratic poems have wildflowers or other flowers as their subject. For instance,

In an 1845 letter to her friend Abiah Root, Dickinson inquires: "Have you made an herbarium yet? I hope you will if you have not, it would be such a treasure to you; most all the girls are making one. If you do, perhaps I can make some additions to it from flowers growing around here."

Emily Dickinson’s teacher, Mrs. Almira H. Lincoln, wrote a book entitled, ‘Symbolical Language of Flowers’. She was just one of the Victorians who believed that each flower or plant had symbolic meaning. For Emily, the jasmine meant ‘passion’ and to give someone a jasmine vine meant, ‘You are the soul of my soul’. Jasmine appeared on the first page of her herbarium as well.

Some of Emily Dickinson’s favorite flowers include: the gentian, the crown imperial, the geranium, the rose and the Indian pipes which adorned the first edition cover of Emily Dickinson’s poems in 1890. Flowers seem to be at the heart of the life of Emily Dickinson. She was wearing a white dress to signify her marriage to the Muse, her artist’s self. She says, ‘The daisy follows soft the sun’ believed to have been written for a man, an imagined lover she called, “Master”. As in her famous unsent letter to “Master,” Emily yearns for ‘the queen’s place’ next to him at night.

Included in my mother's gift of Emily Dickinson's book of poetry to me, at age ten, was a handwritten facsimile of Renunciation in Dickinson's own hand.

RENUNCIATION

There came a day at summer's full

Entirely for me;

I thought that such were for the saints,

Where revelations be.

Entirely for me;

I thought that such were for the saints,

Where revelations be.

The sun, as common, went abroad,

The flowers, accustomed, blew,

As if no soul the solstice passed

That maketh all things new.

The flowers, accustomed, blew,

As if no soul the solstice passed

That maketh all things new.

The time was scarce profaned by speech;

The symbol of a word

Was needless, as at sacrament

The wardrobe of our Lord.

The symbol of a word

Was needless, as at sacrament

The wardrobe of our Lord.

Each was to each the sealed church,

Permitted to commune this time,

Lest we too awkward show

At supper of the Lamb.

Permitted to commune this time,

Lest we too awkward show

At supper of the Lamb.

The hours slid fast, as hours will,

Clutched tight by greedy hands;

So faces on two decks look back,

Bound to opposing lands.

Clutched tight by greedy hands;

So faces on two decks look back,

Bound to opposing lands.

And so, when all the time had failed,

Without external sound,

Each bound the other's crucifix,

We gave no other bond.

Without external sound,

Each bound the other's crucifix,

We gave no other bond.

Sufficient troth that we shall rise --

Deposed, at length, the grave --

To that new marriage, justified

Through Calvaries of Love!

Deposed, at length, the grave --

To that new marriage, justified

Through Calvaries of Love!

Feel free to leave any comments,

Comments

This really was beautifully written.

I'm so glad you enjoyed it. Thanks so much for stopping by!