La Belle Dame Morris (1839-1914)~My Review of Jane Morris: The Burden of History by Wendy Parkins

- Preface

- Introduction

- Scandal - Jane Morris and her men Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Wilfrid Scawen Blunt

- Silence - Her reticence and myth of Indvalidism

- Class - Politics and Socialism

- Icon - Being Mrs. William Morris

- Home - Jane Morris at home and her creativity

Henry James said of Jane Morris, "She was a figure cut out of a missal"

George Bernard Shaw said after meeting her, "She looked as if she had walked out of an Egyptian tomb at Luxor."

In the Introduction: Life and Letters Jane Morris herself asks this question, "Why should there be any special record of me when I have never done any special work?" I wonder what she would say if she knew the lengths that scholars and academics were going to in seeking to answer her? Very simply, Jane Morris's persona is analyzed and disected throughout Rossetti's correspondence, as well as, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt's diaries called Secret Memoirs.

Here are two photographs of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt. The first one on the left is the infamous heartthrob photograph! The right one is what he most likely looked like during his affair with Jane Morris during the late 1880s!

I cannot make up my mind about Mrs. Morris, whether she is really clever or not. I watched her closely and I don't think she knows anything about painting but I like her whether or not, her connection with Rossetti makes her very attractive to me. (Blunt Papers, Fitzwilliam Museum, 7 May, Indian Memoirs, vol. III.56)

Wendy Parkins divides this first chapter, Scandal, into two parts: Firstly, she examines how Dante Gabriel Rossetti represented Jane Morris (both photographed above) as she emerged throughout his writings. For instance, her relationship with Rossetti was subjected to gossip amongst their friends and colleagues at the time, until finally being named in later published works such as Rossetti's correspondence with Jane Morris. Rossetti depicted Jane as a languid vessel for his subsequent emotional and artistic struggles or manipulating him for his affection and attention.

Mrs. Morris interests me like a person risen from the dead. Rossetti was her lover but she gave him up on principle and of course regrets it. Now she is in the third age of woman. If we had met ten years ago it would have been more interesting still . . . These past four days have been like a return to my old life. (Blunt Papers, Fitzwilliam Museum, 19 July 1884, Diaries: 111)

Secondly, Scandal analyzes Jane's affair with Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, as well as, her emotional state. Luckily or not, Blunt's one-sided, close-ended account/viewpoint survives. If only we had Jane Morris's account to read as well. The author uses numerous biography samples to support her finding's on the scandalous Jane Morris. Throughout this study, Parkins will rely heavily on her sources i.e. the correspondence of close friends and colleagues some members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Painter Marie Spartali Stillman dressed as Hypatia photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron

She is absolutely and entirely unlike anyone I have ever loved before. There is nothing material here to love. I hardly desire her more than one might desire a spirit but her eyes inspire me, her voice thrills me to my bones and the touch of her hand is like an electric current. If this is not love I know not what love is - it is more than love, it is an enhancement, for I think of her all day and night except when exorcised by the company of holy men. It is agreed that we are to correspond during the winter but beyond this nothing. (Blunt Papers-Secret Memoirs,vol. XIII: 212, Fitzwilliam Museum)

Reading, Jane Morris: The Burden of History has taught me one thing so far; Blunt pursued Marie while also having an on again off again affair with Jane Morris! When it comes to men and women in relationships, I can see not much has changed since the nineteenth-century! Stillman became an increasing challenge to Blunt, especially after she 'refused' to have sex with him! It seems that after her refusal, Blunt escalates Stillman to an almost untouchable angelic status, whereas, his feelings for Jane at the time concentrated more on the physical and the conquest of her. His curiosity and sexual appetite was quenched by Jane Morris.

My most representative recollection of (Rossetti) is of his sitting beside Mrs. Morris, who looked as if she had stepped out of any one of his pictures, both wrapped in a motionless silence as of a world where souls have no need of words. And silence, however poetically golden, was a sin in a poet whose voice in speech was so musical as his - hers I am sure I never heard. (Francillon, R.E., 1914: 172, Mid-Victorian Memories)

He that tells a a secret is another's servant (Jane Morris's keepsake book- Blunt's Papers, Add. 45351C) Shown below is a photograph of a page taken from Jane Morris's keepsake book with writing from Tennyson's The Princess (photo included in Jane Morris: The Burden of History by Wendy Parkins). The book was a gift to Rosalind Howard (Castle Howard Archives).

In this second chapter sub-headed 'Silence', Wendy Parkins interprets various accounts of Jane Morris's 'silent invalidism' as she calls it, mentioned in other's correspondence, and recent studies of Victorian invalidism. Parkin's believes there is a connection between speaking and silence, action and immobility, illness and vitality as it pertains to Jane Morris and whether she was the embodiment of all these things. Rossetti, Blunt, George Bernard Shaw and Henry James certainly believed so as evidenced in their written records.

Included in this chapter is one of Jane's letter's written to her close friend Rosalind Howard dated 1878, "As to your charge against yourself of chaffing my husband, of course, I never resented it in the least. I am glad you spoke out, for now we shall never misunderstand each other again, shall we? I shall see you whenever I can, and when I can't I shall think of you, and always as long as I live shall remember our stay in Italy as one of the happiest bits of my life. What more can I say, except that I shall always be yours most affectionately, Jane Morris."

Perhaps, 'silence' is not that golden after all! I'm sure Mrs. Morris spoke out whenever and however was necessary. Certainly, her remaining and now preserved correspondence is proof of her voice.

The silence of the invalid or immobility of an artist's model gives us the viewer or reader a blank canvas on which to draw our conclusions about Jane Morris as the Victorian clichéd lady on the sofa. Was she purposefully depicted in a form of femininity as the genteel invalid, the silent muse whom men believed should be kept in her place? Jane Morris eluded interpretation and became an anomaly instead.

The third chapter deals with the subject of Class as in status. For Jane Morris that meant being discovered and plucked out of working-class obscurity and into William Morris's middle-class world of respectability. Jane Morris could be viewed as a real-life Eliza Doolittle ... enter George Bernard Shaw and Pygmalion; but that's a story for another time!

Wendy Parkins relies heavily on two sources by The Morris's close friend J.W. Mackail's diaries and two volumes of The Life of William Morris, to analyze the relation between class, social formations, and the personal identity of Jane Morris. Specifically, the signifigance of her early life, her behaviour and her attitude as an adult.

Towards the end of the chapter on 'Class,' Jane Morris uses her class status as Mrs. Morris politically to help support Wilfrid Scawen Blunt's campaign as a Conservative candidate for Camberwell North during 1885. She says, "I see they have accepted you as a candidate. When do you begin canvassing? Let me know if I can help you in that and I will with pleasure." (Faulkner 1986: 10) She became a political activist and though her opinion of Socialism differed from her husband William Morris, she maintained meaningful friendships with suffragettes, feminists, and women who supported themselves as artists or writers.

The fourth chapter deals with the subject of Jane Morris as Icon. Poet Ernest Rhys said of Jane after seeing her in the audience of a performance of her husband, William Morris's The Tables Turned where he was the Archbishop of Canterbury, "before the curtain went up, I had the sensation of seeing a figure, which might have stepped straight out of a Pre-Raphaelite picture, passing through the audience. It was Mrs. Morris, whose superb tall form, long neck, and austere, handsome, pale features looked more queenly than any Guinevere or Cleopatra."

Wendy Parkins takes a fresh view of Jane Morris's Iconic status by examining her life story as a woman who forged an identity through her role as artist's model, reconstructing her identity to an unrealistic level of heroic status- placing her as a woman out of time giving her a sense of displacement imposed upon her by the men in her life, deemed by the Victorian society and culture of which she lived.

"unique in face and figure, she was a queen, a Prosperine, a Medusa, a Circe-but also, strangely enough, a Beatrice, a Pandora, a Virgin Mary." ( William Bell Scott 1892: 61)

Another aspect of Jane Morris's status as Icon appears in her 'celebrity status.' She was well known in her day as a result of the international growth of Pre-Raphaelitism, and Rossetti's work. Jane became the face of Pre-Raphaelite beauty to which she replied,

"I was not much flattered, but immensely amused."

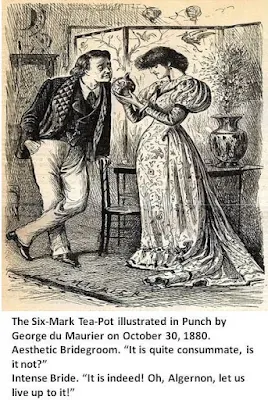

Wendy Parkins also eludes to Jane's dress and fashion style influencing Aestheticism partly due to her depictions in the painting's of her husband and Rossetti. For instance, George du Maurier's illustrations of a tall brunette woman in a long white flowy dress were featured prominently in the local paper Punch. The woman looked very much like Jane Morris herself and friends!

The final and fifth chapter 'Home,' sees Wendy Parkins analyzing Jane Morris as mother, friend, and craftswoman while emphasizing the importance of home as the center of creativity, hospitality, and intimate family life. Through letters and archival records William and Jane Morris can be understood from four viewpoints:

William Morris's study for La Belle Iseult (I cannot paint you, but I love you), Val Prinsep's story of seeing William Morris reading Dickens's Barnaby Rudge aloud to Jane, George Boyce's recollection of a Jane Burden (pre-marriage) at Godstowe during her engagement to William Morris, and finally the wedding of William and Jane Morris as recollected by friend's Edward Burne-Jones and J.W. Mackail.

One of my favorite excerpt's is a reminiscence by Jane and William's daughter, May Morris, "Father and Mother came down to Kelmscott Manor unexpectedly yesterday and father had taken the cooking into his own hands with a grand flourish of trumpets. You wd have laughed to see him this morning settled or rather unsettled at his designing and every five minutes hastening into the kitchen to raise the lid of his stew-pot & commenting in anxious tones as to the probabilities of an eatable dish being the result! They both asked after you & whether you had passed the time down here pleasantly. Mother enquired whether you had eaten well, adding suspiciously, "I hope you did not starve him?" I retorted with wounded spirit that though I might have laid the foundations of a life-long dyspepsia in you by unskillfully prepared viands, your attack on them was so spirited as to entirely do away with her starvation-supposition which I considered a gratuitous insult." (Blunt Papers, British Library, Add. 50541)

Wendy Parkins asks if there can be a link drawn between Jane Morris's femininity, silence, status as Icon, juxtaposed against wanting to be viewed as more of a creative woman in her own right? For Jane, her creativity was taught and handed down mostly to her daughter, May Morris. For, it was May who was able to forge a successful career as craftswoman and designer working for her father's company, 'Morris & Co.' May went on to manage the textile division while Jane became an active participant in the household business instead.

He that tells a a secret is another's servant (Jane Morris's keepsake book- Blunt's Papers, Add. 45351C) Shown below is a photograph of a page taken from Jane Morris's keepsake book with writing from Tennyson's The Princess (photo included in Jane Morris: The Burden of History by Wendy Parkins). The book was a gift to Rosalind Howard (Castle Howard Archives).

In this second chapter sub-headed 'Silence', Wendy Parkins interprets various accounts of Jane Morris's 'silent invalidism' as she calls it, mentioned in other's correspondence, and recent studies of Victorian invalidism. Parkin's believes there is a connection between speaking and silence, action and immobility, illness and vitality as it pertains to Jane Morris and whether she was the embodiment of all these things. Rossetti, Blunt, George Bernard Shaw and Henry James certainly believed so as evidenced in their written records.

Included in this chapter is one of Jane's letter's written to her close friend Rosalind Howard dated 1878, "As to your charge against yourself of chaffing my husband, of course, I never resented it in the least. I am glad you spoke out, for now we shall never misunderstand each other again, shall we? I shall see you whenever I can, and when I can't I shall think of you, and always as long as I live shall remember our stay in Italy as one of the happiest bits of my life. What more can I say, except that I shall always be yours most affectionately, Jane Morris."

Perhaps, 'silence' is not that golden after all! I'm sure Mrs. Morris spoke out whenever and however was necessary. Certainly, her remaining and now preserved correspondence is proof of her voice.

The silence of the invalid or immobility of an artist's model gives us the viewer or reader a blank canvas on which to draw our conclusions about Jane Morris as the Victorian clichéd lady on the sofa. Was she purposefully depicted in a form of femininity as the genteel invalid, the silent muse whom men believed should be kept in her place? Jane Morris eluded interpretation and became an anomaly instead.

The third chapter deals with the subject of Class as in status. For Jane Morris that meant being discovered and plucked out of working-class obscurity and into William Morris's middle-class world of respectability. Jane Morris could be viewed as a real-life Eliza Doolittle ... enter George Bernard Shaw and Pygmalion; but that's a story for another time!

Wendy Parkins relies heavily on two sources by The Morris's close friend J.W. Mackail's diaries and two volumes of The Life of William Morris, to analyze the relation between class, social formations, and the personal identity of Jane Morris. Specifically, the signifigance of her early life, her behaviour and her attitude as an adult.

Towards the end of the chapter on 'Class,' Jane Morris uses her class status as Mrs. Morris politically to help support Wilfrid Scawen Blunt's campaign as a Conservative candidate for Camberwell North during 1885. She says, "I see they have accepted you as a candidate. When do you begin canvassing? Let me know if I can help you in that and I will with pleasure." (Faulkner 1986: 10) She became a political activist and though her opinion of Socialism differed from her husband William Morris, she maintained meaningful friendships with suffragettes, feminists, and women who supported themselves as artists or writers.

The fourth chapter deals with the subject of Jane Morris as Icon. Poet Ernest Rhys said of Jane after seeing her in the audience of a performance of her husband, William Morris's The Tables Turned where he was the Archbishop of Canterbury, "before the curtain went up, I had the sensation of seeing a figure, which might have stepped straight out of a Pre-Raphaelite picture, passing through the audience. It was Mrs. Morris, whose superb tall form, long neck, and austere, handsome, pale features looked more queenly than any Guinevere or Cleopatra."

Wendy Parkins takes a fresh view of Jane Morris's Iconic status by examining her life story as a woman who forged an identity through her role as artist's model, reconstructing her identity to an unrealistic level of heroic status- placing her as a woman out of time giving her a sense of displacement imposed upon her by the men in her life, deemed by the Victorian society and culture of which she lived.

"unique in face and figure, she was a queen, a Prosperine, a Medusa, a Circe-but also, strangely enough, a Beatrice, a Pandora, a Virgin Mary." ( William Bell Scott 1892: 61)

Another aspect of Jane Morris's status as Icon appears in her 'celebrity status.' She was well known in her day as a result of the international growth of Pre-Raphaelitism, and Rossetti's work. Jane became the face of Pre-Raphaelite beauty to which she replied,

"I was not much flattered, but immensely amused."

Wendy Parkins also eludes to Jane's dress and fashion style influencing Aestheticism partly due to her depictions in the painting's of her husband and Rossetti. For instance, George du Maurier's illustrations of a tall brunette woman in a long white flowy dress were featured prominently in the local paper Punch. The woman looked very much like Jane Morris herself and friends!

The final and fifth chapter 'Home,' sees Wendy Parkins analyzing Jane Morris as mother, friend, and craftswoman while emphasizing the importance of home as the center of creativity, hospitality, and intimate family life. Through letters and archival records William and Jane Morris can be understood from four viewpoints:

William Morris's study for La Belle Iseult (I cannot paint you, but I love you), Val Prinsep's story of seeing William Morris reading Dickens's Barnaby Rudge aloud to Jane, George Boyce's recollection of a Jane Burden (pre-marriage) at Godstowe during her engagement to William Morris, and finally the wedding of William and Jane Morris as recollected by friend's Edward Burne-Jones and J.W. Mackail.

One of my favorite excerpt's is a reminiscence by Jane and William's daughter, May Morris, "Father and Mother came down to Kelmscott Manor unexpectedly yesterday and father had taken the cooking into his own hands with a grand flourish of trumpets. You wd have laughed to see him this morning settled or rather unsettled at his designing and every five minutes hastening into the kitchen to raise the lid of his stew-pot & commenting in anxious tones as to the probabilities of an eatable dish being the result! They both asked after you & whether you had passed the time down here pleasantly. Mother enquired whether you had eaten well, adding suspiciously, "I hope you did not starve him?" I retorted with wounded spirit that though I might have laid the foundations of a life-long dyspepsia in you by unskillfully prepared viands, your attack on them was so spirited as to entirely do away with her starvation-supposition which I considered a gratuitous insult." (Blunt Papers, British Library, Add. 50541)

Wendy Parkins asks if there can be a link drawn between Jane Morris's femininity, silence, status as Icon, juxtaposed against wanting to be viewed as more of a creative woman in her own right? For Jane, her creativity was taught and handed down mostly to her daughter, May Morris. For, it was May who was able to forge a successful career as craftswoman and designer working for her father's company, 'Morris & Co.' May went on to manage the textile division while Jane became an active participant in the household business instead.

Here's my copy and what the book looks like.

Comments

It's expensive so be prepared. Thanks for stopping by and commenting!

How wonderful to know that. Jane Morris was such a fascinating woman.I'm so glad you could stop by and read my review. Thanks so much for taking time to leave a comment.

What a fascinating life Jane Morris led. She came from very humble beginnings but did very well for herself. It's interesting to read about what the 'upright Victorians' got up to. There were so many affairs going on especially with the middle class on the art scene.

Not so different from today then! :-)

Thanks for sharing.

I know,I completely agree! Fascinating woman, fascinating times they lived in! Thanks for commenting!

Hi Hermes,

Wow! Half-price! I know we will probably never know the truth. Thanks so much for stopping by and commenting. I hope you enjoy the book. I look forward to reading your review :)