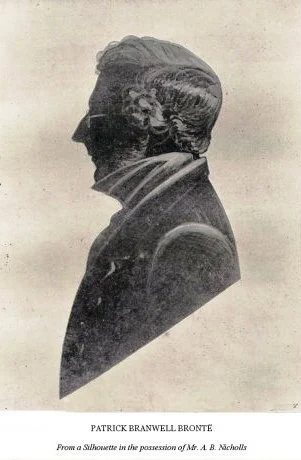

(Patrick) Branwell Bronte: The Lost Bronte: (26 June 1817–24 September 1848)

Daphne du Maurier described Branwell, ‘Branwell Bronte was an appropriate biographical subject because he was mad: he was destroyed not by a thwarted love affair, as he and his biographers claimed, but by his inability to distinguish truth from fiction, reality from fantasy; and who failed in life

because it differed from his own infernal world.’ The Infernal World of Branwell Bronte by Daphne du Maurier,(p. 10).

Branwell’s famous older sister, Charlotte Bronte says of

him, “I

do not weep from a sense of bereavement…but for the wreck of talent, the ruin

of promise, the untimely dreary extinction of what might have been a burning

and shining light. My brother was a year my junior. I had aspirations and

ambitions for him one-long ago-they have perished mournfully…There is such a

bitterness of pity for his life and death-such a yearning for the emptiness of

his whole existence as I cannot describe.” (Letter from Charlotte

Bronte to her friend William S. Williams, the day after Branwell’s funeral on

October 2, 1838)

A Life Misunderstood

On 26 June, 1817, the fourth child of Patrick Bronte and Maria Branwell Bronte was born during the early hours of the morning in Thornton. This newborn boy was given the honour of two names because for Patrick and Maria having a son was a particularly welcome moment. He was named Patrick, after his father, and Branwell, after his mother’s maiden name. Though, there always seemed to be some confusion over which name came first. The day after his birth, his three sisters: Maria, Elizabeth and Charlotte, were invited down to Penzance to the Kipping House so they could join a large party of ladies who fussed over the little girls. In no time the parents sorted out the confusion over their son’s name and on 23 July,1817, at a ceremony at the Old Bell Chapel Patrick Branwell Bronte was baptized. His godparents were Elizabeth Firth’s father and stepmother, close friends of The Bronte’s.

He was small for his age but good looking, with his father’s nose and a high forehead. He had poor eyesight, he wore glasses and he wore his hair, the reddest in the family, long in an artistic fashion.

In 1838, Bramwell Bronte wrote three poetical essays, including two long poems, about the death of his sister Maria, whom he named, 'Caroline' in these essays. Here is just the beginning. Its twelve pages long in its entirety!

It was during this time

that Charlotte, Branwell, Anne and Emily wrote stories together; surviving as ‘juvenilia’

called the Glass Town Federation. Branwell and

Charlotte invented the kingdom of Angria, while Emily and Anne created the

world of Gondal. They became obsessive about their imaginary worlds, drawing

maps and creating lives for their characters and featured themselves as the

‘gods’ (‘genii’) of their world. Their stories are in tiny micro-script, as if

written by their miniature toy soldiers.

Branwell

wrote the history of these sagas in, ‘The History Of The Young Men From Their

First Settlement To The Present Time’ which can be found in a copy of

The Young Men’s magazine containing an introduction where Branwell gives an

account of the toy soldiers that gave rise to the game resulting in creating

imaginary worlds. Glass Town was originally a place of fantasy, assumed the

characteristics of the nineteenth-century city. A map of the real explorations

in northern and central Africa between (1822-1824), while the hero of the saga,

the Duke of Wellington gives a foreshadowing of what would later become an

established genre of alternative histories.

Emily

and Anne stopped contributing to the Glass Town stories at some point so they

could concentrate on creating their own imaginary world of Gondal. I wonder if

this was simple retaliation or sibling rivalry? Sadly, the chronicles of this

imaginary place written in prose were lost and only the poems survive.

These

were the days of childhood writing of imaginary kingdoms containing different

elements no matter how incongruous in real life could be brought together to

form stories. However, as the Bronte siblings aged, they went in albeit

different literary directions. Somehow, keeping in touch with each other and

always analyzing and critiquing each others’ work.

In

1829, at the age of twelve years old, Branwell produced his first verse play, ‘Laussane:

a Dramatic Poem’ by Young Soult, set in France in 1423 which charted

the restoration to power of the exiled Count Laussane. According to Charlotte

Bronte, Young Soult was a favorite character Branwell made up that she did not

like. She called him an ‘insulting caricature with grandiose

aspirations.’ Branwell responded

by saying, ‘this Poem is an exceedingly rambling and irregular meter and contains a

great many things for which he ought to be punished Young Soult-I wrote it

while drunk.’

More

poems were to follow in the same fashion. Six months later, as Young Soult, he

wrote another dramatic poem, ‘Caractacus,’ telling the story of the ancient

Briton’s betrayal to the Romans. Six months after ‘Caractacus’ he produced ‘The

Revenge,’ another medieval tragedy in 3 Acts,’ similar to ‘Laussane.’ On the

title page of both poems he quoted himself, as Captain John Bud saying:

'In

dramatic poetry the chief thing to be attained is an excellence in describing

the passions and in proportion as this excellence is attained so are we to

judge of the merits of the piece'. (J BUDS synopsis of The Drama Vol I p130)

In

1831, Bronte father, Patrick, supported the Whigs’ Reform Bill to the surprise

of his Tory friends. The bill would disenfranchise the boroughs and enfranchise

some of the new towns halving the property qualifications for registration as a

voter. Patrick defended himself against charges of becoming an enemy to the

establishment.

A

year later, on 17 May 1832, Charlotte wrote to Branwell, ‘As usual…because to

you I find the most to say. Lately I had begun to think that I had lost all the

interest which I used formerly to take in politics but the extreme pleasure I

felt at the news of the Reform-bill’s being thrown out by the House of Lords

and of the expulsion or resignation of Early Grey, convinced me that I have not

as yet lost all my penchant for politics.’

In

June of 1831, her letter brought an unexpected visit home by Branwell where he

and the family discussed politics and his progress with his writing. He was

working on something he called, ‘The History of the Young Men’ as well as ‘Letters

from an Englishman’ completed in August. With the death of the real person he

based his character of Young Soult upon; Branwell stopped writing for the time

being.

Branwell

took the reign’s creating, ‘Branwell’s

Blackwood Magazine’ eventually handing it over to Charlotte, turning to

newspaper writing instead. Although, there is only one example of this, ‘Monthly Intelligencer’ from March to

April 1833, it is evident that newspaper writing gave Branwell a greater

opportunity to explore his political interests by reporting debates and the

progress of events as they unfolded.

Branwell

was known by family and friends as being somewhat of a painter. He enjoyed

painting with his father regularly in oils and the family believed he would

become a distinguished painter one day. It was during the summer of 1833, family

friend, Ellen Nussey visited and found Branwell getting ready to paint a

portrait of his sisters which he would bully into sitting and posing for him.

According to Mrs. Gaskell, Branwell painted himself in the portrait but not

happy with it he scrubbed himself out leaving just his three sisters: Anne,

Emily, and Charlotte.

Known as the 'Pillar Portrait' because Branwell's figure can be seen dimly beneath the pillar.

A photograph of a portrait in oils, now lost, painted by Branwell in 1833. It depicts all four Brontes: Anne, Charlotte, Branwell, and Emily but it was destroyed by Arthur Bell Nicholls because the likenesses were too poor to preserve.

On

January 27, 1837, Branwell established the Haworth Operative Conservative

Society during a meeting in the church Sunday school room. He acted as

secretary for that meeting and was appointed chairman for the second quarter of

the year. The objectives of the society were ‘to maintain loyalty to the King

attachment to the connection between church and State respect for the independence

and prerogatives of the House of Lords and a proper regard for the Commons

House of Parliament.’

With

his father’s support, on 22 February, 1837, Branwell called and chaired a

meeting of the inhabitants of the township in the school room to petition

Parliament to repeal the Poor Law Amendment Acts of 1834 whose measures were

just beginning to be put into practice in Yorkshire. Charles Dickens Oliver Twist comes to mind. The Act

ended outdoor relief, which had been administered locally by the parish vestry

and had supplemented the incomes of the poor during periods of unemployment for

need. Poor Law unions, administered centrally by commissioners in London, were

formed by parishes and those who through old age, infirmity or unemployment were

no longer able to support themselves could only obtain assistance by residing

in the workhouse. Sadly, this also meant separation of the sexes: separating

husbands and wives, parents and children which angered everyone. Patrick and

Branwell addressed the assembled crowds, ‘upon that occasion neither speakers nor

hearers had met to promote the interest of party, but to plead the cause of the

poor.’ Branwell read and moved the petition, which was carried

unanimously and sent to one of the local members of Parliament and the

Archbishop of Canterbury for presentation to the Houses of Commons and Lords respectively.

News coverage included The Times making Patrick Bronte a

bit more popular than he liked.

It

is fair to say that the life of Branwell Bronte was a turbulent one; known for

his drinking and career failings in the railway and somewhat as an author. He was

never as successful as his famous sisters. In childhood, Branwell shined as the

golden boy for his poetry and writing but in adulthood he was overshadowed and surpassed

by his sisters. He struggled to publish his own works as an adult, even with

the help of his sisters; it just never came to fruition. He mainly translated

others works for publication or had the odd poem published in a yearly magazine.

The only way Branwell’s poems would be published was amongst the poems of his

sisters. However, Branwell longed to have editions and volumes of his poetry

and writing published as his sisters would soon enjoy.

One

lasting betrayal of Branwell came from his sisters in 1846 when he discovered

that Charlotte and Emily were planning on contributing their works to a volume

of poetry without asking him to contribute any of his poetry or telling him

about their plans. Branwell found out after receiving a letter in the mail by

mistake discussing publishing plans with Henry Moxon. Branwell was heartbroken

and never recovered; thus adding to his drinking and bouts of unemployment. Charlotte

would only give one reason of explanation, ‘We could not tell him of our efforts for

fear of causing him too deep a pang of remorse for his own time misspent, and

talents misapplied.’

Branwell's health soon declined and no one noticed just how ill he had become. Often drunk or hung over it only made sense that his body would be affected. He began suffering from fainting fits and bouts of influenza. Branwell talked about his 'misspent life, his wasted youth' while his father pleaded with his son to seek salvation with urgency before his death.

At about nine o'clock on Sunday, 24 September, 1848, with the Bronte family gathered in his room he remained conscious until the end. After about twenty minutes Branwell's entire body convulsed and he fell back dead into his father's arms. He was thirty-one years old.

Thorp

Green

by Patrick Branwell Bronte

I sit, this evening, far away,

From all I used to know,

And nought reminds my soul to-day

Of happy long ago.

Unwelcome cares, unthought-of fears,

Around my room arise;

I seek for suns of former years

But clouds o'ercast my skies.

Yes-Memory, wherefore does thy voice

Bring old times back to view,

As thou wouldst bid me not rejoice

In thoughts and prospects new?

I'll thank thee, Memory, in the hour

When troubled thoughts are mine-

For thou, like suns in April's shower,

On shadowy scenes wilt shine.

I'll thank thee when approaching death

Would quench life's feeble ember,

For thou wouldst even renew my breath

With thy sweet word 'Remember'!

From all I used to know,

And nought reminds my soul to-day

Of happy long ago.

Unwelcome cares, unthought-of fears,

Around my room arise;

I seek for suns of former years

But clouds o'ercast my skies.

Yes-Memory, wherefore does thy voice

Bring old times back to view,

As thou wouldst bid me not rejoice

In thoughts and prospects new?

I'll thank thee, Memory, in the hour

When troubled thoughts are mine-

For thou, like suns in April's shower,

On shadowy scenes wilt shine.

I'll thank thee when approaching death

Would quench life's feeble ember,

For thou wouldst even renew my breath

With thy sweet word 'Remember'!

Sources

(1886) by Francis A. Leyland, Volume 1.

Patrick Branwell Bronte

by Alice Law, 1923.

The Infernal World of Branwell Bronte by Daphne du Maurier

Feel free to leave comments,

Comments

A fascinating insight into Patrick Branwell Bronte's life. So what's the matter with living in a dream world? I do it all the time. :-)

Such a pity he died young, what other joys could we have now if he'd lived. Sadly the death of his sisters was typical of the time they lived, we are lucky to have what remains of their gifted but short lives.

Thank you for sharing.

It was wonderful learning a bit more about Branwell, the man, instead of focusing on how he fit in or not with his sisters.

I tend to agree with you, Kevin, about a dream world ;) If only!

Yes, who knows what other creative works we lost out on. Thank you both for taking the time to comment.