Product Details

- Hardcover: 780 pages

- Publisher: Knopf (September 26, 1995)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 0394585313

Synopsis:

Since his death in 1896, William Morris has come to be regarded as one of the giants of the nineteenth century. But his genius was so many-sided and so profound that its full extent has rarely been grasped. Many people may find it hard to believe that the greatest English designer of his time, possibly of all time, could also be internationally renowned as a founder of the socialist movement, and could have been ranked as a poet together with Tennyson and Browning.With penetrating insight, Fiona MacCarthy has managed to encompass all the different facets of Morris's complex character, shedding light on his immense creative powers as artist and designer of furniture, fabrics, wallpaper, stained glass, tapestry and books, and as a poet, novelist and translator; his psychology and his emotional life; his frenetic activities as polemicist and reformer; and his remarkable circle of friends, literary, artistic and political.

In “How I Became a Socialist”, Morris himself wrote: “The hope of the past times was gone, the struggles of mankind for many ages had produced nothing but this sordid, aimless, ugly confusion; the immediate future seemed to me likely to intensify all the present evils by sweeping away the last survivals of the days before the dull squalor of civilization had settled down on the world.”

Preface

While Morris’s whole is much greater than the sum of his parts, the various parts are in and of themselves so wonderful that it is easy to become lost in one of his many facets. Not only was he a designer, handicraft artisan, manufacturer, businessman, political activist, conservationist and man of letters, he was successful enough in these (and other) endeavours for each to have become the focus of specialist attention.

Perhaps more than any other Victorian celebrity, MacCarthy says, “he has been the victim of the keepers of the flame, people anxious to play down or even up his revolutionary Socialism”. In a more modern mode, MacCarthy discusses his private life, and refers to earlier reluctance as “a conspiracy of memory”, a “conspiracy of silence”.

Morris’s unconventional domestic arrangements have only slowly come to light. As MacCarthy says, “The full extent of his unhappiness, and his fortitude and generosity in facing it, is only now being revealed.” We now know, for instance, that his wife, Jane (widely known in the literature as Janey), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were lovers from 1867 or 1868 to 1875, and that Jane and Wilfrid Scawen Blunt were lovers for about a decade to 1894.

One advantage of MacCarthy’s biography is that she has been able to make use of some revelations and to access research on William Morris. It is no surprise that MacCarthy’s work draws on material from 'The Collected Letters of William Morris' edited by Norman Kelvin, the commentary of which provides a rich biographical resource. Morris’s letters are famously cold and unrevealing, and MacCarthy supplements them with his literary works, which are treated as confessional pieces that shed light on his inner state of mind. Here she accepts the autobiographical significance of literary writings such as The Earthly Paradise. The result is a comprehensive life that examines all aspects of this complex and multifaceted man.

Anecdotes about Morris abounded. One well-known story has him angrily accusing the press of willful neglect at a party also attended by Oscar Wilde saying,“The press ignores me”, he claimed, “There’s a conspiracy of silence about my book”; to which Wilde retorted “Why not join it, Morris?”

For instance, Sir Edmund Beckett called him a “poetic upholsterer”, and Rossetti also called him the “upholsterer & author of Earthly Paradise”. In his “The Tables Turned”, Morris was himself described by Lord Tennyson as “a stumpy little fool in blue”. Henry James described him in 1869 as “short, burly, and corpulent, very careless and unfinished in his dress … [with] a very loud voice and a nervous restless manner and a perfectly unaffected and business-like address”. He was indeed a bluff, cheery and hearty man. His attitude to art was a robust and one of common sense. In his own time, he was known for his physical strength, his fits of anger, his untidy appearance and unconventional dress, his love of the simple rural life, his unconventional marriage, and his passion for angling. This is all covered in detail by MacCarthy.

As a manufacturer, a capitalist-socialist who employed labour, Morris has been seen as a hypocritical and contradictory figure. He himself drew a great deal of pleasure and satisfaction from his work, but one has to ask whether the same was true of his employees. There is a contradiction between his belief in creative, satisfying, and independent work, and the practices of Morris & Co., or the Firm, in which his designs were produced by tedious and repetitive work, is an issue that MacCarthy does not tackle so well.

A biographer must break a single lifetime into sections that can be dealt within single chapters. MacCarthy says: “Morris’s life unfolded in cycles”, and that “His activities surge onwards in overlapping phases, each of them approximately five years in duration”. His life is thus broken down into distinct periods. For instance, “The middle 1870s were Morris’s dyeing years, the late 1870s his weaving years”, while the 1890s are defined as the “post-Socialist” period. However, some of his activities lasted throughout his life.

William Morris From Birth to Marriage

Morris was born on March 24th, 1834, in Walthamstow a quiet village east of London. Much later in life, in 1883, he was to describe Walthamstow as “a suburban village on the edge of Epping Forest … once a pleasant place enough, but now terribly cocknified and choked up by the jerry-builder”.

His father was an affluent bill broker, whose shares in the Devonshire Great Consolidated Copper Mining Co., usually known as the Devon Great Consols, underwrote the family’s affluence. After his father’s death, some shares were sold, but thirteen were put aside for each of the nine children for when they came of age. Annual dividends from Morris’s thirteen shares were to provide him with the independence and comfort of a private income.

According to his daughter May, Morris was raised “in an atmosphere of intelligent housekeeping of the old style homemade beer and bread, real butter and real cream and the like … There were well-stocked gardens and orchards, horses and cows and pigs and poultry.” When he was six, his prosperous parents moved to Woodford Hall, a house situated on about fifty acres of parkland and a hundred acres or so of farmland. He attended a preparatory school from the age of nine, from where, in 1848, he went to Marlborough College. His father had died in 1847, and the family moved to the smaller but still genteel Water House in 1848.

He entered Exeter College, Oxford in 1853. Though he arrived after the heyday of the Oxford Movement, religious thought was still very much in the air. He met Edward Jones, later Sir Edward Burne-Jones who was to be a lifelong friend. Both Morris and Burne-Jones were attracted to a High Church Anglo-Catholicism, and both initially intended to become clergymen. Two early influences were John Ruskin and in particular his “On the Nature of Gothic”, and Thomas Carlyle, especially Past and Present. And from Ruskin, Morris learned of the Pre-Raphaelites.

In the summer of 1855, Morris and Burne-Jones visited France, where, in Le Havre, they decided to pursue careers in art rather than the church. Morris decided to devote his life to architecture (Burne-Jones decided to become a painter). Also in 1855, on coming of age, Morris came into what was, for a young and single man, a small fortune.

Having graduated, he began to work in George Edmund Street’s architectural firm in 1856. An Anglo-Catholic and leading Gothic architect, Street was a significant influence (MacCarthy does not however pursue this particular line of thought). There he met Philip Webb, who became a very close friend. Street’s office moved from Oxford to London, and to London went Morris where, in August 1856, he moved into rooms in Bloomsbury with Burne-Jones, and through Burne-Jones met Rossetti. After a few weeks in Bloomsbury, Morris and Burne-Jones moved to Red Lion Square, where they led a Bohemian lifestyle within a subculture of male camaraderie.

Having fallen under Rossetti’s dominating influence, Morris determined to become a painter and, in late 1856, resigned his position at Street’s firm. MacCarthy depicts Rossetti as a sadistic bully, and Morris as the butt of cruel jokes. This may be true, but saying that “He had a southern European callousness” weakens her point, as does her observation about “the southern melancholy that ebbed and flowed so tragically in his life”.

In 1857, Morris met one of Rossetti’s discoveries, Jane Burden, a famous indeed the archetypal Pre-Raphaelite beauty. Jane Burden was from a poor family, but despite their social differences, they were married in 1859. It was not a happy marriage, and seems to have always been loveless on her part. According to MacCarthy, “Rossetti’s looming presence over the liaison of the two sexually inexperienced and socially disparate young people helped to confirm the marriage in its doom.” Morris was also known for his fits of rage, perhaps epileptic in origin, which cannot have helped. Jane quickly became an invalid, although her symptoms are usually seen as neurotic. Not yet thirty, she took to a sofa in 1869 and in effect never left it, except, it must be said, in her husband’s absence.

The Defence of Guenevere, which was published in 1858, contains a number of poems now often counted as among Morris’s best. MacCarthy says: “at their best they have a brilliance, a freshness and a quirkiness that Morris’s poetry did not achieve again”. One of the characteristics of his verse is the use of stops in the middle of the line and the combination of realism and experimental meters. He took to anapaests, which served to provide a rolling flow to his verse, and has a recognizable style which was apparent from his first published pieces. An example can be seen in works such as “The Haystack in the Floods”, one section of which goes:

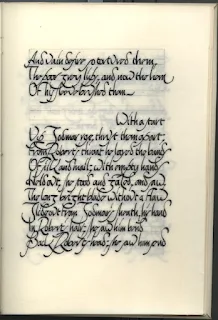

Written in Morris' hand: the poem stanza below

With a start

Up Godmar rose, thrust them apart;

From Robert’s throat he loosed the bands

Of silk and mail; with empty hands

Held out, she stood and gazed, and saw,

The long bright blade without a flaw

Glide out from Godmar’s sheath, his hand

In Robert’s hair; she saw him bend

Back Robert’s head; she saw him send

The thin steel down; the blow told well,

Right backward the knight Robert fell,

And moan’d as dogs do, being half dead,

Unwitting, as I deem: so then

Godmar turn’d grinning to his men,

Who ran, some five or six, and beat

His head to pieces at their feet.

Whatever its merits, The Defence of Guenevere was panned by the critics and not received well by the public either. Morris did not publish any more verse until The Life and Death of Jason in 1867.

In the meantime, the newlyweds could not live in Morris’s bachelor accommodation at Red Lion Square. Morris commissioned the building of a new home, Red House (it was built of red brick) in Kent, which enabled Webb to set up his own practice. Mr and Mrs Morris moved into the house, which his friends named the Towers of Topsy, in 1860. Red House was an architectural success, and has been seen as a major development in British domestic architecture. MacCarthy’s description of the house becomes lyrical. “The house is plain and functional, beautiful and homely, with the simple solid structure and respect for its materials that recommended it to modern movement architects in the 1930s, whose paradigm building it became. But Red House is also playful, willful, an amalgam of surprises, gables, arches, little casements of a size to shoot an arrow through.” Here and elsewhere, MacCarthy demonstrates a sense of place and landscape that is one of the great strengths of her biography.

In the early 1860s, Morris’s income from his inheritance declined rapidly and the idea of a business that would manufacture items for domestic life was floated. This idea was further stimulated by the need to decorate the Red House interior. This led, at least in part, to the foundation of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. in April 1861 the prospectus includes the names of Ford Madox Brown, Burne-Jones, Rossetti and Webb. In its first years it specialized in ecclesiastical work and especially stained glass and then received two prestigious non-ecclesiastical commissions for St James’s Palace in 1866-1867 (and once again in 1880-1881) and the South Kensington Museum in 1867. It was dissolved in 1875, reorganized as Morris & Co, and was to remain of central importance to Morris for the rest of his life. Morris spent perhaps the happiest years of his life at Red House. Both of his two beloved children, May and Jenny, were born during these years. However, in 1865, he sold it and moved to London in order to better run his business. Jane, MacCarthy writes, would have been aware that “the move entailed a definite loss of social status”.

The Earthly Paradise was published in four parts and three volumes from 1868 to 1870 (Morris was embarrassed by what he termed its “elephantine bulk”). As we have already seen, MacCarthy accepts the idea of using of the verse to shed light on the life. The Earthly Paradise is not read much, if at all, today, but both were extraordinarily successful with the Victorian reading public. For the rest of his life, Morris was known as “the author of The Earthly Paradise”. Of the two poems, perhaps the prologue of The Earthly Paradise is best known.

Of Heaven or Hell I have no power to sing,

I cannot ease the burden of your fears,

Or make quick-coming death a little thing,

Or bring again the pleasure of past years,

Nor for my words shall ye forget your tears,

Or hope again for aught that I can say,

The idle singer of an empty day.

Another extract suggests escapism, and looks forward to some of the themes of News from Nowhere.

A page from News from Nowhere circa 1890

Forget six counties overhung with smoke,

Forget the snorting steam and piston stroke,

Forget the spreading of the hideous town;

Think rather of the pack-horse on the down,

And dream of London, small and white and clean,

The clear Thames bordered by its gardens green;

The stress on the marriage until about 1870 is marked only by the lack of a single surviving letter to Jane from before March 1870. After this, some accommodation in which he seems to have agreed to turn a blind eye to her relationship with Rossetti must have been reached, and letters are preserved. But the poetry conveys some idea of his personal anguish and suffering during those earlier years.

Many of the love poems were written to Jane, which must have been obvious to her husband. MacCarthy helps to fill in the details of a sad marriage. Morris rented Kelmscott Manor, the house now so closely associated with his name, together with Rossetti from 1871. “The house in the country,” MacCarthy says, “was an attempt to find a civilized modus vivendi for Morris, Janey and Rossetti, giving the triangle the stamp of permanence and at least a veneer of respectability”.

In Conclusion

Tennyson died in 1892. Despite his politics, Morris was suggested as the new poet laureate. He was approached by a member of cabinet and asked whether he would accept the position if offered it. Morris said he was honored, but could not possibly accept. He had been radicalized to such an extent that he could no longer see himself working with the establishment.

Morris had initially begun collecting early printed books for their woodcuts, or for information on subjects such as dyeing. Morris turned to books from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, even to Pliny. He later developed an interest in printing and type-setting, which in turn led to the Kelmscott Press. His last piece of great artistic workmanship was the 1896 Kelmscott Chaucer, which contains eighty-seven pictures by Burne-Jones. This was the final masterpiece of his multiform production.

He died in 1896. A doctor said that he died because of “simply being William Morris, and having done more work than most ten men”. Drawing on a great wealth of primary and secondary materials, Fiona MacCarthy has provided a vivid picture of this radical conservative and romantic socialist.

Please feel free to leave any comments,