A Pre-Raphaelite Tale: Tis Better To Have Loved And Lost Than Never To Have Loved At All

"It seems to me when I look at her working, or too ill to work, and think of how many without one tithe of her genius or greatness of spirit have granted them abundant health and opportunity to labor through the little they can or will do, while perhaps her soul is never to bloom, nor her bright hair to fade; but after hardly escaping from degradation and corruption, all she might have been must sink again unprofitably in that dark house where she was born. How truly she may say, 'No man cared for my soul.' I do not mean to make myself an exception, for how long have I known her, and not thought of this till so late—perhaps too late." Rossetti writing to Allingham

This is a tale about the true love between

two paired souls destined to meet and fall in love forever. Though, Dante

Gabriel Rossetti might have listened to his mother, Frances Polidora Rossetti, when

she said of her family, “I always had a passion for intellect, and my desire

was that my husband and my children might be distinguished for intellect; but

now I wish they had a little less intellect, so as to allow for a little more

commonsense.”

The young twenty-something Dante Gabriel Rossetti was

constantly keeping ‘someone’ in mind to pose as the Damozel for his ‘infamous’

painting ‘The Blessed Damozel.’ He hadn’t found her yet but was just on the verge

of discovery when he told his Brotherhood mates, ‘She must be stately, sober,

serious, tall, and possess a wondrous length of limb. Her features must be

strong, individual, and she must have personality rather than beauty. A pretty

woman would, of course, never, never do.”

He was becoming quite melancholy in a state of rapidly growing

frustration upon the fear that ‘Nature had never made as lovely a woman as he

could imagine’ but being a man he did not give up his quest.

One day, a brief member of the Brotherhood, Walter Deverell,

came bounding into Rossetti’s studio standing on his head, leaping about

jumping on the furniture! Rossetti quickly reprimanded him before interrogating

Deverell as to the reasons for such unmanly behavior! The all important Deverell

responded, ‘I have found her!’

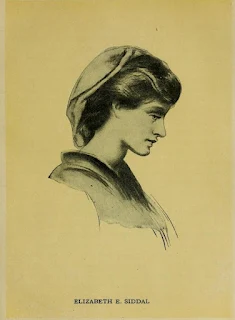

Who was she? This presumed Damozel? Her name was Elizabeth

Eleanor Siddal, and she was an assistant to a millner and dressmaker in Oxford

Street. She was seventeen years old in the year eighteen hundred and fifty. She

stood five feet eight inches tall and weighed one hundred twenty pounds. Her

hair was of a marvelous, coppery, low tone, with features resembling those of

Sappho. For the twenty two year old

Rossetti, whether or not the dressmaker’s wonderful assistant had intellect and

soul did not matter. He was not going to be swept off his feet by the tale this nineteen

year old Walter Deverell told. Rossetti simply sneezed and calmly

continued his work at the easel, making a note of the shop location where the ‘find’

was located. Once Deverell left Rossetti’s studio, all semblance of this calm

exterior left him and two hours later, alone, he put aside his brushes and

palette, put on his hat, and walked rapidly toward Oxford Street. Once he found

the shop, he walked past it, first on one side, then on the other just before

mustering up the courage to enter on a fictitious errand. Miss Siddal was there. He stared at her; she looked at him

in half-disdain. Suddenly his knees grew weak: he turned and fled. The next day Walter Deverell showed up at the shop on Oxford

Street accompanied by his mother, a customer of the shop. He wanted to speak to

her but lost his nerve and also fled. However, Walter’s mother, stayed and put

forth a business proposition to this soon to be Damozel, Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal;

luckily for Dante Gabriel Rossetti or

there might never have been the pairing of two souls.

Elizabeth Siddal came from a very poor family. Her father

was an auctioneer who had lost his voice, and she was glad to earn more money

she was receiving by posing for the artists. She was already a model, setting

off bonnets and gowns, and her first idea was that they wanted her for

fashion-plates. Apparently, Mrs.Deverell did not exactly lead her to believe

that this was not the case! So, she

posed for the Brotherhood at Rossetti’s studio, wearing a gown as angels are

supposedly draped dressed in Paradise.

Mrs. Deverell was there for assurance and all went well that

day. Elizabeth Siddal was observed by the Brotherhood to be a dignified young

woman, proud, with a fine but untrained mind. Her knowledge of literature, she

explained, 'was Tennyson’s poems because she found them on some sheets of paper

that were wrapped around a pat of butter she bought to take home to her mother.' Her general mood was one of silent good-naturedness, peppered with a dash of

pride with just enough innocent curiosity to know how the picture was getting

along. Miss Siddal was reserved because she realized that she could never talk

as picturesquely as she could look. She was eager and anxious to learn and

Rossetti set about educating her. He found himself loving her with a mad

devotion. The other members of the

Brotherhood respected this frank devotion and it did not become a matter of

competition but merely admiration.

Within a week of their meeting, ‘The House of Life’ began to take shape.

He wrote to her and for her, and always and forever she was his model. The

color of her hair got into his brush, and her features were entwined in his

heart. He called her “Guggums’” or “Gug.” Occasionally, he

showed impatience if any one slightly doubted the divinity of his ‘Guggums.’ He loved her with an absorbing passion, loved

her for her wonderful physical beauty, and what she may have lacked in

intelligence did not seem to bother him. In turn, she accepted his love as if

it were her destiny, as if it had always been hers. She was not agitated under

this burning impetus: no, she just calmly and placidly accepted it as a matter

of course. According to Burne-Jones, ‘Love is never mutual; one loves and the

other consents to be loved.’

The House of Life by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1901

Sonnet The House of Life by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Page 1

Sonnet The House of Life by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Page 2

Prospectus for The House of Life by Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

1901

Henriette and Rik Roland Holst had quite a number

of special editions such as this edition of Rosetti edited by Charles

Nypels. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sonnets and songs towards a work to be called the house of life. Maastricht 1926

The Rossetti clan accepted her because Dante Gabriel

obviously loved her so. Although, he did tell his sister Christina, the great

poetess, who he believed was smarter than his ‘Guggums’, “never to converse with Miss Siddal on great themes.”

John Ruskin added his endorsement of Elizabeth Eleanor

Siddal calling her, ‘a glorious creature.’

Even though we know Rossetti’s depictions of Siddal are too retouched,

painted as if to perfection, they must be inaccurate in everyone else’s eyes.

His brother William said, ‘tall, finely formed, with lofty neck; regular, yet

uncommon, features; greenish-blue, unsparkling eyes; large, perfect eyelids;

brilliant complexion, and a lavish wealth of dark molten-GOLD HAIR.’ (I thought she was a red head not a blonde—Rossetti’s

inaccuracy and perfection maybe).

Elizabeth Siddal had a manner of morbid languor and

dreaminess that was put on, some said, for her lover like a Greek gown, and surely

encouraged by him and pictured in his Dantesque creations. For Rossetti, always and forever, she was the

Beata Beatrix. He became consumed in writing poems to her or painting her. If they were separated for even a day he

wrote her a letter, and demanded that she should write one in return to which

she gently demurred. She did take drawing lessons often while posing would work

with her pencil and paper.

John Ruskin was so pleased with her work that he offered to

buy everything she did. He paid her one hundred pounds a year and took

everything she drew. This only proves Ruskin’s generosity not the worth of her work.

The engagement between Rossetti and Siddal lasted nine years.

Five years on, in 1855 Madox Brown asked Rossetti, ‘Why do you not marry her?’

Rossetti explained what everyone around them already knew. Even though she was

not quite well enough to live independently and not exactly smart enough for a

career of her own, she deferred to her lover, she adopted his likes and dislikes,

even developing his own prejudices. You see, he told Madox Brown, ‘We may dwell and camp in Bohemia, but it

is a very poor place in which to settle down.’

It seemed as if the volatile Bohemian lifestyle was taking

its toll on Elizabeth Siddal’s health. Although, she had always been sickly,

once her relationship with Rossetti became consistent, Siddal seemed to fall

into decline. Her spirits lost their buoyancy, she grew nervous when required

to pose sometimes several hours at a time.

Rossetti’s love for Miss Siddal was sincere in its

insincerity. Love became secondary over his supreme impulse to make art. In the end, their nine year engagement, with

its uncertainty, forgetfulness, vacillating absent-minded habits of erratic

genius to deal with, simply wore out the life of this beautiful creature. When

Siddal’s doctor told Rossetti that his lovely lily was fading, he married her

immediately; swearing he would nurse her back to life. He gave her the home they had so long spoken

of. It consisted of three small rooms, one all hung with her own drawings and

no others. He made sure she was surrounded by the friends she liked best, he gave

little parties and told friends they were never happier. Though it seems that

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal suffered from Neuralgia which today would be defined

as Chronic Fatigue Disorder; a nerve disorder that was treated during the

nineteenth century by Laudanum. Siddal took it to relieve the all over body

nerve pain, becoming dependent on it.

On 10 February, 1862 she dined with her husband and Mr.

Swinburne at a nearby hotel. Rossetti then accompanied her to their home,

leaving her there alone so he could go to deliver his weekly lecture at the

Working Men’s College. Returning two hours later, he found her unconscious from

an overdose of laudanum. She never regained consciousness, breathing her last

but a few short hours later.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti blamed himself, cursed himself, for

not being home with her when she died. He was convinced that he could have

saved her, ‘I should have worked through

her hand and brain.’ Of course, that

was just his grief talking.

He gathered all the poems he had written to her, including, ‘The

House of Life’ and tying them up with one of the ribbons she had worn, placed

the precious package in her coffin. So the poems were buried with the woman who

inspired them, his muse. The two souls temporarily

physically separated until seven years later when Elizabeth Siddal’s body was

exhumed, by Rossetti, so he could recover the poems. You see, grief gave way to calm reflection.

The river of his love was just as deep running through a turbulent current. It is not for us to scrutinize why he

recovered the poems or buried them in a fit of momentary madness and grief but

just to be grateful for the opportunity of reading them for ourselves; if only

to remember two fated souls that could not be parted by death.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The Kiss

Sonnet VI from "The House of Life: A Sonnet Sequence"What smouldering senses in death's sick delay

Or seizure of malign vicissitude

Can rob this body of honour, or denude

This soul of wedding-raiment worn to-day?

For lo! even now my lady's lips did play

With these my lips such consonant interlude

As laurelled Orpheus longed for when he wooed

The half-drawn hungering face with that last lay.

I was a child beneath her touch,--a man

When breast to breast we clung, even I and she,--

A spirit when her spirit looked through me,--

A god when all our life-breath met to fan

Our life-blood, till love's emulous ardours ran,

Fire within fire, desire in deity.

The Kiss: the two lovers in the bedroom, a woodcut from page 501 of Chaucer, Geoffrey: “The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer [William Morris, Kelmscott Press]” (1896)

Sources

Little journeys to the homes of great lovers

(1916) Author: Hubbard, Elbert,

1856-1915; Hoyle, John T. (John Thomas), b. 1873, ed; Roycroft Shop, printer, Volume: 13, Publisher:

New York : Wm. H. Wise & Co., Language:

English.

William

Sharp’s A Record and a Study, 1882, Macmillan and Company

Please feel free to leave any comments,

Comments

Love of this sort can and does occur though it is certain types that love this way. In reality Lizzie could be a trying person and Rossetti, with his huge, flowing personality, must have eventually felt curbed by her neurotic ailments which were her way of controlling him and holding him to her when he began to stray. She used to manage some long and arduous journeys at times when inclined despite her ailments! As for her paintings, I actually handled and looked at many in the Bodleian library in Oxford as well as reading her truly sad poems in the original script...a thrilling experience. I love her pictures. Well, it wasn't an easy love affair, but when was love ever easy?

I can understand her worries, fears, ill health and wanting to be loved so much that you become willing to put up with a man like Rossetti and that circle of friends.